The first case of SCC

In late 2007, one of my Nigerian does developed what I thought was an infected sore under her tail. It didn’t really make sense, there didn’t seem to be a way for her to have gotten an injury there. The vet treated her with antibiotics. She was four years old, light-colored with a pink tail – classic squamous doe, unbeknownst to me. The sore worsened and spread and a different antibiotic did nothing; a few weeks later I drove her 90 minutes to a real livestock vet. When we got there – a fairly large mixed practice – one of the small animal vets looked at her because the livestock vet was tied up. I answered all the questions I had already answered, about the supposed infection, the antibiotic treatment, etc. To the vet’s credit after a couple of minutes of listening she said to the vet tech – “go and get John.”

The grizzled old livestock vet, who raised dairy goats himself, stuck his head in the door. “That’s cancer,” he said. And it was, squamous cell carcinoma, confirmed by biopsy a few days later. There was no real treatment for it then. “Just keep her comfortable.”

The doe lived about six more months, with the cancer spreading in ugly bright red lumps and ulcerations that would occasionally erupt with pus, but for much of that time she was very comfortable, affectionate and adorable, enjoying her special treatment and tolerating the occasional antibiotic treatment for secondary infection. But as the cancer grew outside it was also growing inside, and after about six months she began to grunt and strain when she pooped: the internal growth was choking off the area around her rectum. One day instead of just grunting she gave a sharp cry of pain.

The next day a very kind vet friend of mine came out to the farm and put her down. She was and remains one of my all-time favorite does, well-bred, productive, an excellent milker with a wonderful disposition. How strange, how odd, I had never heard of a doe with cancer, especially one so young. But strange things happen all the time. And that was it, or so I thought. Bad luck.

More Cases of SCC

But within a couple more years two more Nigerian does were dead of SCC. All three were very closely related. One was a half-sister of the first doe. I asked the vet, didn’t he think it was a strange coincidence? He did think it was a bit odd, but doubted any genetic component. Two of the does, the sisters, were pink-tailed, mostly white does. And fair skin is known to be associated with squamous in goats, as it is in people. The third, who was an aunt of the other two, was black and white, with a dark tail. But she had come from Eastern Washington, and lived a couple of years there before I bought her. Unlike Western Washington where I live – which is notoriously gray and rainy – Eastern Washington is bright and sunny with very hot summers. A good place to accrue a lot of UV damage. So maybe that was the start of it.

Still, it never really made sense to me. Why would the Nigerians get it, and not my LaManchas, many of whom were blond and pink-tailed? Why would we get it at all, living in such a soggy, moderate climate? But for several years nothing else happened, and I put it out of my mind. Then the daughters and granddaughters of the first three does began to reach the age of 4, 5, 6, and again it popped up. Never in any of the LaManchas, never in my other Nigerian lines.

Three more cases appeared over the next few years, all descended directly from the first does. Around this time I was at an appraisal session where the appraiser was standing next to me chatting to a breeder and somehow the subject of squamous came up. “Oh,” he said, “you mean the Nigerian cancer?” He had seen it all over the country, very prevalent in the breed, so much so that when he said “the Nigerian cancer,” the breeder he was talking to nodded. Yes, the Nigerian cancer.

At this point it just didn’t seem possible to me that there was not a genetic component. I decided to try to investigate further. I posted a survey and got 80+ responses from people who had had squamous in their Nigerian herds. One of the questions was whether or not the breeder raised another breed of goat, as I do. About 15 people who replied yes got a follow-up question – had they had any squamous in this other breed? 100% replied no.

Not very scientific and not a big survey but it did seem to support the idea of a genetic component. I started combing through the pedigrees of affected goats I knew. The first thing I discovered was that adgagenetics was pretty useless for this purpose, because there is very little information about foundation animals. Except for the noble breeders who have taken the trouble and expense to register long-dead animals, adgagenetics hits a brick wall at about 2008, when the registry began to be flooded with its newest, and now far and away most popular, breed.

Looking for Genetic Clues: The Missing Link Database

So with the help of a friend I began to put together a small database, a kind of a missing link database, which though woefully incomplete bridges some of the gaps between ADGA and the major foundation animals. And I was shocked by what that revealed. For one thing, Nigerians are very much more inbred than adgagenetics shows, which would certainly elevate the chances for a widespread genetic issue to take root. I wondered if I might find a single ancestor, a single animal like Frosty Marvin – perhaps the most popular Nubian sire ever – who introduced the fatal defect G6S into the breed.

But that didn’t seem to happen, and partly by missing some basic information, I gave up the idea that I would discover an animal to whom SCC seemed to trace back. And of course SCC is very different from G6S: it’s something that occurs across almost every species, and it’s very true that it’s likelier to occur in fair-skinned animals. And it can and usually does occur spontaneously, because of environmental and other risk factors. But it is also true that over time and especially recently, researchers have uncovered breed-specific genetic links to squamous.

The Haflinger Study at UC-Davis

When I accidentally discovered a study in Haflingers that had identified a genetic link to SCC – and subsequently a dna test developed at UCDavis – it was the first time everything made sense. If you aren’t familiar with Haflingers, they are a sturdy Austrian breed of horse. They are a color breed – every Haflinger is blond (colors ranging from pale blond to a reddish chestnut) and flaxen-maned, so that eliminated the color component.

These horses were all basically the same color, and yet some of them were getting squamous (an ocular form of it) at almost 6 times the rate of others. It seemed to be concentrated in a certain line, the so-called “A” line. All registered Haflingers are named by gender – male names always start with the same letter as their sire, and female names start with the same letter as the dam. I only happen to know that because I have a Haflinger – luckily he is from the “W” line. UC-Davis discovered a mutation in the “A” line. It was recessive, so a horse could be an unaffected carrier. But horses with two copies of the mutation developed squamous at a much higher rate, and were also younger at onset.

How Squamous Develops

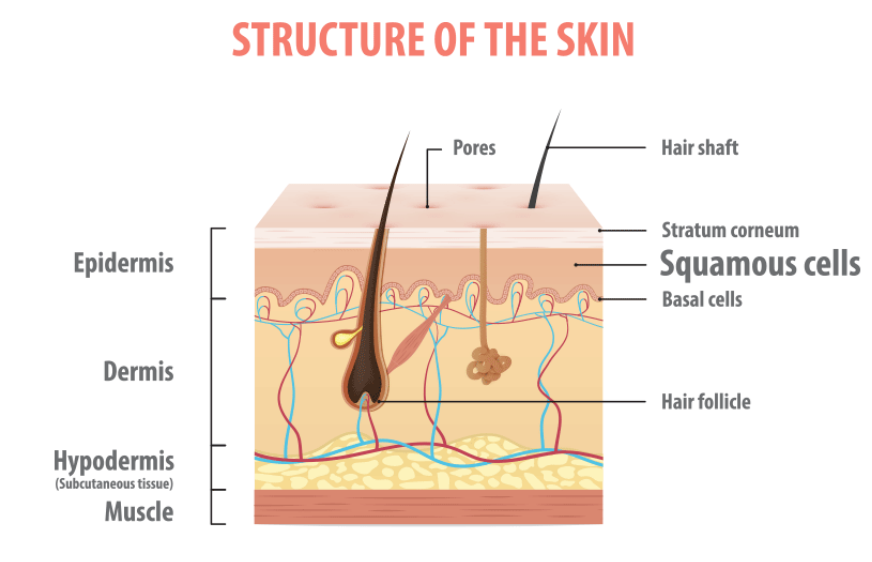

In order to develop squamous an animal has to sustain a certain amount of UV damage. It doesn’t usually show up in a yearling or a 2- or 3-year-old because the damage needs to build up. A dark-skinned animal has natural protection against UV damage because the dark coloration is a kind of sunscreen. That’s why squamous, and skin cancer in general, is much more common in white people than it is in black people. And the perineal form, the so-called “under-the-tail” cancer that plagues Nigerians, is much more common in does with unpigmented tails.

Over time and with repeated exposure UV damage can become cancerous. A light-skinned animal sustains much more UV damage. An animal in a hot sunny environment sustains much more damage.

But there is also the possibility of an inherited component. Haflingers with the mutation had a variant in their makeup which rendered them unable to repair DNA damage. So any damage they sustained was much more likely to cause cancer. There is a rare genetic condition in people called xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) which also drastically impairs the body’s ability to repair UV damage. People with XP are 10,000 times more likely to get skin cancer. And at very young ages.

I may be wrong but I believe there is something similar to the Haflinger mutation in the Nigerian breed. And as we put together our little database, and as more people let me know about animals they had had with SCC, it became clear that there were a lot of affected animals with Twincreeks in their pedigrees. Now Twincreeks – with such stellar bucks as Baywatch and Braveheart – is a very popular line. Even so, it seemed disproportionate. One name popped up repeatedly.

Twinks Pixie

Raha Acres Twinks Pixie – two-time National Champion and the foundation doe of the Twincreeks herd. Of the six animals I have had with SCC, all went back directly to Twinks Pixie. I know of quite a few others as well. But I also knew Pixie had lived to age 11 – past the age at which an animal would normally develop SCC. So it seemed really unlikely that even if she had been carrying a genetic mutation similar to the Haflinger mutation that she would have developed SCC, which is one of the other things that makes squamous so slippery in Nigerians.

I often hear people say things like, if it’s genetic why didn’t her daughter/son get it? Leaving out the many ways in which genetics is not so simple as that, a daughter or son may have had dark skin, which ordinarily is a strong defense against SCC, a permanent sunblock that prevents damage from occurring in the first place.

Then one day recently I was clearing out one of the storage rooms in my barn and I came across a stack of old Ruminations magazines, the much-loved miniature goat publication started by Kathleen Claps and continued by Cheryl. K. Smith. Who knows why but I picked out one from 2006 and flipped it open and lo and behold Kellye Bussey from Twincreeks had written an obituary for Twinks Pixie, who died that spring.

Pixie had been euthanized at age 11 after developing skin cancer. Even more surprising, she was a dark-skinned doe. “Yes,” wrote Bussey, “dark-skinned goats can get it, too.”

I have often heard people say that SCC affects their best does, or their most productive milkers. If it goes back to a doe like Twinks Pixie, that would make sense. She was an extraordinary doe, ahead of her time, and her sons and daughters went into the best herds around the country.

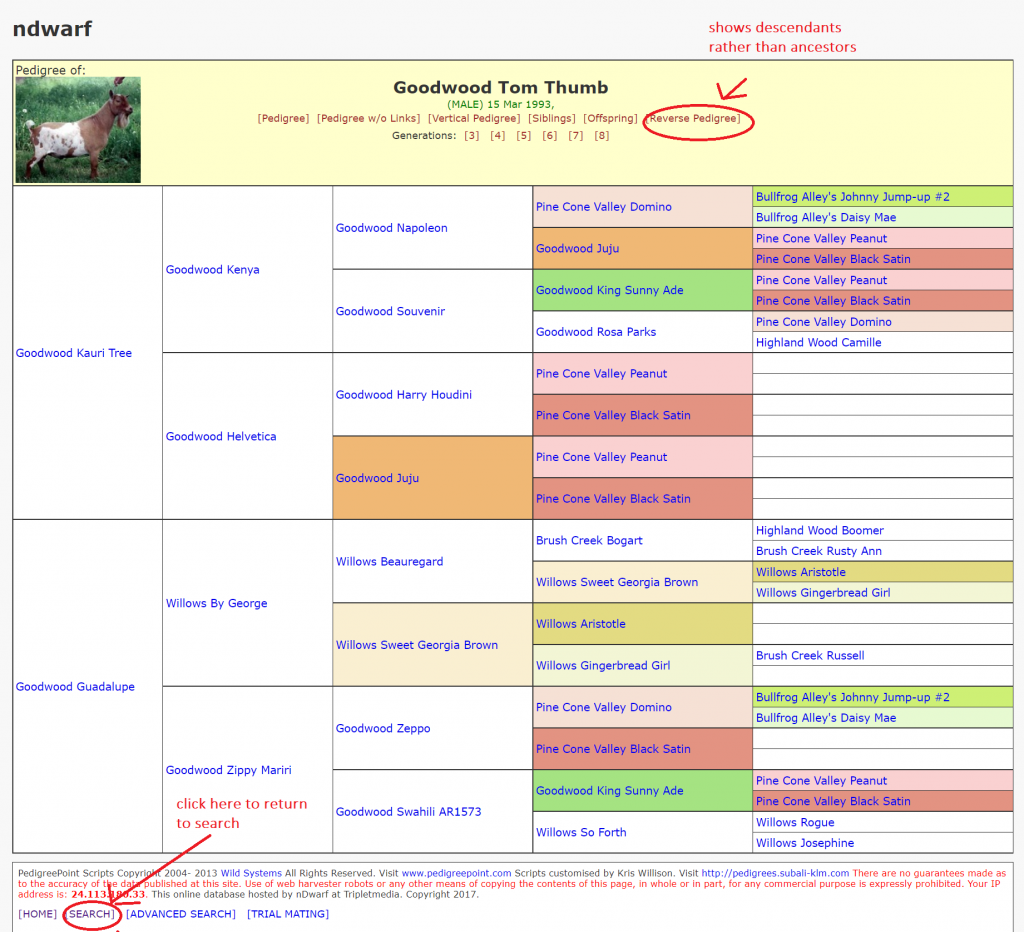

Her genes are everywhere in the breed, even a quick glimpse at her reverse pedigree shows that:

There is no proof that there is a genetic component to SCC in Nigerians. And there is no proof that there is any connection to the Twincreeks lines, which did so much to advance the breed. I certainly wouldn’t point it out except for the fact that Kellye Bussey herself made it public.

In any case, whether or not there is a genetic component to it, it isn’t anyone’s fault. And if – a big if – squamous in Nigerians is connected to a genetic mutation, and if that mutation is recessive – like G6S and the Haflinger mutation – then in order for Twinks Pixie to have been affected, she would have had to inherit one copy from each of her parents. Which would mean that it first popped up somewhere further back in the line.

More research and more information can only help.

Research or Submit a Goat

Do you have a registered Nigerian, living or dead, with squamous? Send us the registered name and we will add it to our spreadsheet, which will be kept confidential and used only for research purposes. Would you like to investigate your animal’s pedigree but you’re hitting a roadblock and can’t go back further than adgagenetics takes you? Send us the name and whatever other information you have and we may be able to help you reconstruct the pedigree.

Prefer to investigate yourself, for whatever reason? The missing link database is a good place to start.

QUESTIONS? CONTACT: herronhilldairy@gmail.com

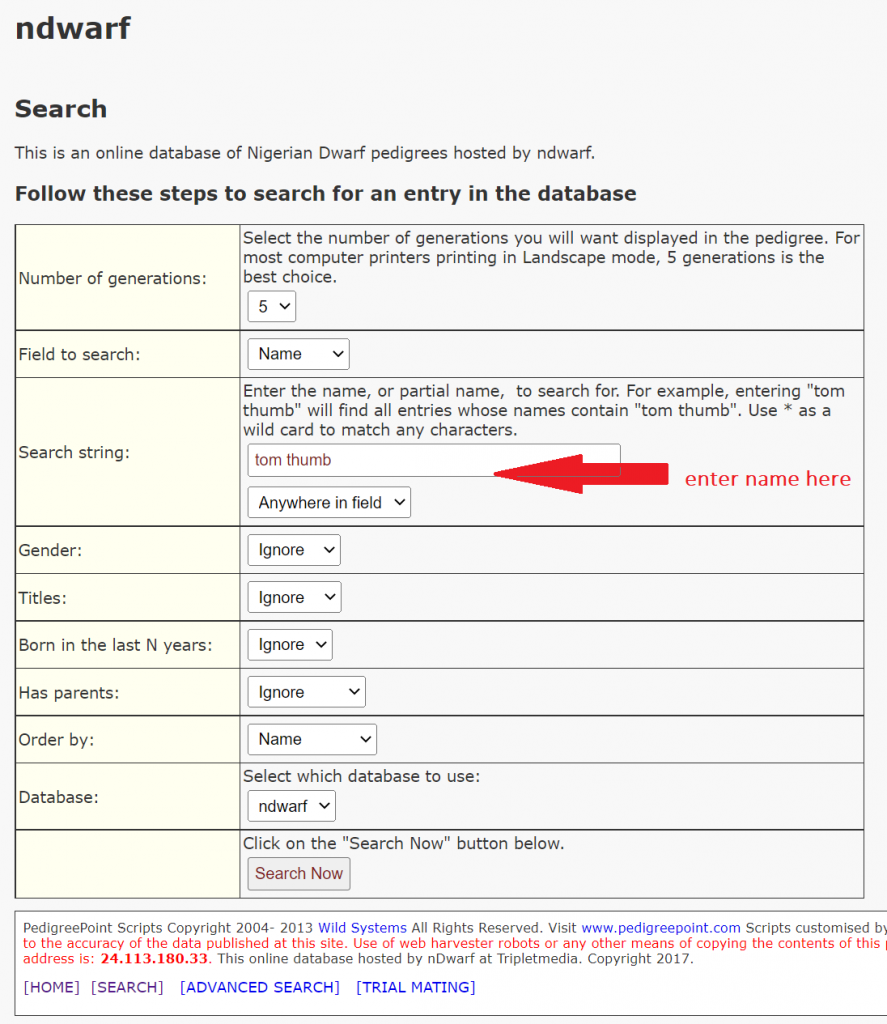

Quick Tips on Searching the Database

It can be a bit quirky, usually only on the first search, though. If your search returns a blank page, refresh and try again. Please let us know if you find an error or duplicate, and remember that this database is very far from complete. Thanks to all the people who submitted animals for it.

There are several search options on the basic search page and more on the advanced page, but quickest and easiest is just to search by name and ignore the other parameters.

The individual animal pages offer a variety of clickable links, including links across the top which go to offspring, siblings, etc. Reverse pedigree shows descendants rather than ancestors, which can be very interesting. And at bottom left of the page you can return to search.